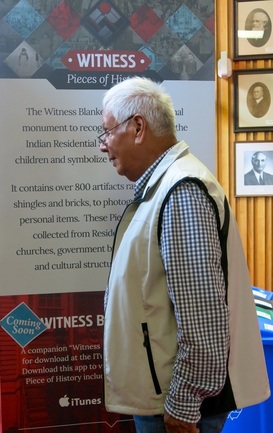

The Witness Blanket Project 2014

In 2011, Kwagiulth artist Carey Newman envisioned an installation called the Witness Blanket. In 2013, Carey and team members travelled across Canada collecting stories and objects from residential school survivors and their families. Now completed and touring Canada, the Witness Blanket is over eight feet tall and 40 feet long. Cedar frames hold the objects in place.

Between 1840 and 1996 over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were forced to leave their homes and live at residential schools. The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission began recording survivor stories in 2008. This commission funded the collection tour and construction of the Witness Blanket.

Between 1840 and 1996 over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were forced to leave their homes and live at residential schools. The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission began recording survivor stories in 2008. This commission funded the collection tour and construction of the Witness Blanket.

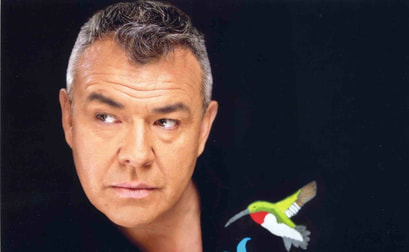

Carey Newman has a mission.

He wants to create awareness about the effects of the Indian Residential School era in Canada.

He wants to create awareness about the effects of the Indian Residential School era in Canada.

“I wasn’t sure how the Witness Blanket would work out,” he recalls, “survivors aren’t comfortable talking about it.” Carey saw a shift when his father, Victor Newman, decided to speak at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings in Victoria. Victor spoke privately with his family present in April 2012. Later, they visited the two sites where Victor attended residential schools. Carey had a pleasure of watching his father gradually change, become lighter, less troubled by the past.

In contrast, Carey’s own stress level mounted as he puzzled over design and assembly details. His workshop filled up with nearly 900 items collected from survivors, cultural buildings and abandoned residential schools. “I felt obligated to the people who gave them," he says, “and the stories they told.” Carey paid proper respect to the objects through prayers and smudging, while sorting, organizing and mounting. The artist knew the success of the project hinged on the many fragments coming together harmoniously to tell their story and help with the healing. He attended to his own emotional and spiritual health through traditional medicines and ceremonies. “My wife Elaine was very understanding and an immense support,” Carey says.

In contrast, Carey’s own stress level mounted as he puzzled over design and assembly details. His workshop filled up with nearly 900 items collected from survivors, cultural buildings and abandoned residential schools. “I felt obligated to the people who gave them," he says, “and the stories they told.” Carey paid proper respect to the objects through prayers and smudging, while sorting, organizing and mounting. The artist knew the success of the project hinged on the many fragments coming together harmoniously to tell their story and help with the healing. He attended to his own emotional and spiritual health through traditional medicines and ceremonies. “My wife Elaine was very understanding and an immense support,” Carey says.

|

For many years, Victor Newman’s motto about his days at residential school was “forgive and forget." But now things have changed. Connecting with other survivors and speaking out about his experiences has been a healing journey. Victor was seven and his younger brother five, when the priest arrived at their home in New Westminster. His mother was working at the canning factory and his father away fishing. “Get your clothes,” said the priest, “you’re coming with me." |

Victor recalls the trauma of the event and the long journey by car and steamship to Sechelt Indian Reservation School. On arrival, they were scrubbed and their hair cut. Coal oil was poured on their heads. “It was very unpleasant,” recalls Victor.

Initially unsure about the success of the Witness Blanket project, Victor was drawn in by the excitement of the collection process. His wife Edith Newman and her friends spent endless hours sewing and assembling pieces. “It was a good feeling watching them work, but some things were difficult for me to look at.” Victor felt supported by his family and the counsellors close at hand. “They watched me closely to make sure I was doing OK with all the memories and emotions,” he says.

Edith Newman met Victor while working on a fishing boat in 1970. They were married soon after. Trained as a teacher, Edith home-schooled their three children. A textile artist and clothing designer, she is active in community events. Edith arranged for Carey to meet conservators Jane Hutchins and Robert Byers. The couple from Sooke kindly donated their time and talents. “Seeing the completed work fills me with pride and wonder,” Edith says. “Everyone in our family has benefitted from this incredible journey.”

City Hall hosted the completed Witness Blanket during September 2014. Mayor Fortin hopes many people will view the Witness Blanket on its seven-year tour. “It’s important to learn from the past,” he says, “so that atrocities like taking thousands of children from their families and subjecting them to abuse can never happen again.” Mayor Fortin is proud that Victoria’s official Community Plan includes consultations with local First Nations from Esquimalt and Songhees Nations. A number of initiatives that honour and respect the cultural values of First Peoples are underway.

Carey Newman with Shelagh Rogers

Carey Newman with Shelagh Rogers

Journalist Shelagh Rogers (left) was invited to become an Honourary Witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2011. She attended six of the seven TRC National Events and has participated in many dialogues about reconciliation. Her role involves hearing the stories of survivors and bringing them to a wider audience. The broadcaster hosts CBC Radio’s The Next Chapter each week. Excerpts from an email interview follow.

Question: How you find the strength to witness without being overwhelmed by the magnitude and sorrow of the injustice?

Answer: There have been times when I have broken down, dealing with the shame of my country’s crime.Truly, the people who gave me strength were survivors. One elder told me “the real shame would be to feel no shame.” Once, when I was crying listening to a survivor statement, I felt an arm around me. It was an Inuit man from Coral Harbour, Nunavut, who had attended residential school. And here he was comforting me. When that happens, that kind of generosity beyond imagining, strength can be found.

Question: How you find the strength to witness without being overwhelmed by the magnitude and sorrow of the injustice?

Answer: There have been times when I have broken down, dealing with the shame of my country’s crime.Truly, the people who gave me strength were survivors. One elder told me “the real shame would be to feel no shame.” Once, when I was crying listening to a survivor statement, I felt an arm around me. It was an Inuit man from Coral Harbour, Nunavut, who had attended residential school. And here he was comforting me. When that happens, that kind of generosity beyond imagining, strength can be found.

Question: Was there a turning point, a story that captured you, that moved you into this profoundly deep place of empathy for survivors?

Answer: Just before the Apology in 2008, I interviewed three generations of the Jones Family of Nanaimo. John had gone to Alberni Residential School. With him was his daughter Lillian and her daughter Victoria. This was the first time they had sat down together as a family to hear about John’s experience at Alberni. They had the courage to do it with a stranger who was recording them for national broadcast. It was very powerful. Very emotional. There were many tears. John went through hell on every level. I asked if they wanted me to edit the piece. They all said no. Canadians need to hear what really happened. John Jones cracked my heart open.

Question: The monumental size, harmonious colours, textures and shapes of the Witness Blanket give the viewer an immediate sense of order and dignity - in strong contrast to the nature of the story being told. Could you comment on this juxtaposition?

Answer: Well, that is the power of the vision of Carey Newman. You are drawn to the beauty of the piece overall. And individually, the pieces are reminders of the destruction, the abuse, and abduction of children from their families and communities. The genius of the Witness Blanket is that the pieces are stronger together. You come to understand that these objects have borne witness, too. Collectively, they tell a story of endurance, strength, resilience and reconciliation. They have all received, each object, some kind of ceremony, smudging, so that they are prayed over and blessed. And that is another kind of juxtaposition. It is a beautiful piece about the ugliest time in Canadian history.

Answer: Just before the Apology in 2008, I interviewed three generations of the Jones Family of Nanaimo. John had gone to Alberni Residential School. With him was his daughter Lillian and her daughter Victoria. This was the first time they had sat down together as a family to hear about John’s experience at Alberni. They had the courage to do it with a stranger who was recording them for national broadcast. It was very powerful. Very emotional. There were many tears. John went through hell on every level. I asked if they wanted me to edit the piece. They all said no. Canadians need to hear what really happened. John Jones cracked my heart open.

Question: The monumental size, harmonious colours, textures and shapes of the Witness Blanket give the viewer an immediate sense of order and dignity - in strong contrast to the nature of the story being told. Could you comment on this juxtaposition?

Answer: Well, that is the power of the vision of Carey Newman. You are drawn to the beauty of the piece overall. And individually, the pieces are reminders of the destruction, the abuse, and abduction of children from their families and communities. The genius of the Witness Blanket is that the pieces are stronger together. You come to understand that these objects have borne witness, too. Collectively, they tell a story of endurance, strength, resilience and reconciliation. They have all received, each object, some kind of ceremony, smudging, so that they are prayed over and blessed. And that is another kind of juxtaposition. It is a beautiful piece about the ugliest time in Canadian history.

One of Rosy’s favourite objects in the installation is a pebble from the floor of a greenhouse in Inuvik NWT. The pebble was a gift from an Inuit woman. The people had gutted an ice rink operated by a residential school, but left the roof intact. They built raised beds and hauled in topsoil, giving them a source of nourishment and pride. “Gardening was a healing activity that brought the people together,” says Rosy, “and helped transform the difficult memories connected with the rink."

|

Rosy tells an interesting story about a child’s boot she retrieved from the burnt wreckage of a school near Carcross, south of Whitehorse. “The little boot was overgrown with moss and had a palpable energy,” she said. She put it in a ziplock bag and took it back to the hotel room with her other artifacts. That night Rosy had trouble sleeping. “I felt surrounded by a sense of fluttery panic,” she explains, “a nervous energy filled the room.” The next evening, back at home, she put the suitcase with the boot in the guest room. That night, the restless energy returned, both her and her husband experienced sleep disturbances. First thing next morning Rosy took the boot over to Carey. He gently worked with the anxious energy until it finally settled. The shadow box frame that holds the Carcross boot has smudge sticks top and bottom. A healing red medicine ribbon binds the boot. |

|

Jane Hutchins is a textile conservator living in Sooke. Her career spans 25 years and her clients include large and small museums around the world. Jane is a weaver and friend of local textile artist Edith Newman. Hearing about the project from Edith, Jane decided to donate her time and expertise. “This is a really constructive undertaking,” says Jane, “telling the story through tangible objects.” Carey’s artistic vision for the blanket was never compromised, but Jane offered advice on conservation techniques. For example, one of the pieces is a grouping of children’s moccasins. “If one person gives the slippers a gentle touch, that’s fine,” says Jane. “But if contact goes on for several years, there will be damage.” |

Jane’s husband Robert Byers also assisted Carey with the mounting and preservation of objects. He developed a deep appreciation for Indigenous cultures while working at the Royal British Columbia Museum. “I was impressed by Carey’s artistic vision and innovative design skills,” says Robert. Together, they devised archival methods for securing objects.

|

Web Design, Content and Selected Photos:

Kate Cino previewed arts events for 18 years at Boulevard magazine. She has a History in Art degree and Public Relations certificate from the University of Victoria. In 2013, Kate was nominated for a Women in Business “Above and Beyond” award, hosted by Black Press. |

|